Tier 3 Overview: Academic - Social Emotional - Behavioral

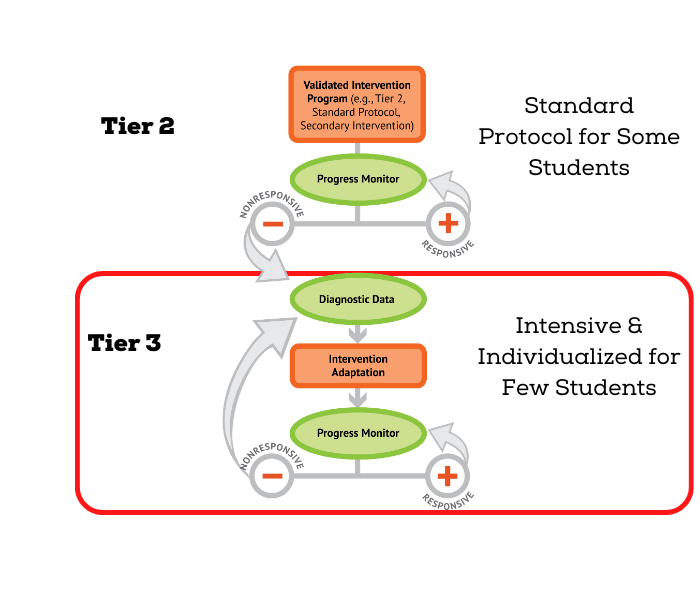

Tier 3 (Intensive Intervention) is the most intensive level of a Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS). At this level, a student-centered team uses a data-based process to design and intensify supports for individual students with significant academic and/or social-emotional-behavioral needs.

Research suggests that approximately 5–10% of students may require this level of support, including some students with disabilities (Fuchs et al., 2008; NCII, 2013). In Rhode Island, Tier 3 intensification is guided by Data-Based Individualization (DBI)—a structured, data-driven process that increases intervention intensity and individualization based on student response.

- Students who have not responded to effective Tier 2 interventions delivered with fidelity

- Students whose screening data indicate an urgent or sudden need

- Students with IEPs who are not making adequate progress toward their goals

For students with the most intensive social-emotional and behavioral needs, Tier 3 may include a wraparound, multidisciplinary team approach that considers the whole child and may involve community partners.

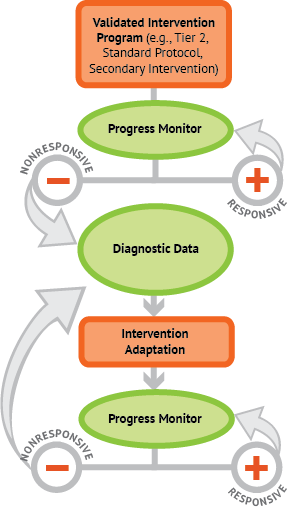

Data-Based Individualization (DBI)

DBI integrates validated interventions and assessments through a continuous improvement cycle. The five steps below guide teams in intensifying support based on student data.

Validated Intervention Program

The DBI process begins with a validated intervention platform delivered to a group of students in a standard way. Often called Tier 2, or a standard-protocol intervention, this platform provides targeted instruction in a specific skill or a set of skills (e.g., phonemic awareness, vocabulary, math problem-solving, social skills, self-regulation) matched to students' needs and delivered with fidelity. Any student (e.g., including students with disabilities) who has the targeted need(s) has access to the intervention. This intervention is in addition to, not in place of, core instruction. Student behavior will not change if the adults in the system do not change the environment and their behavior in support of students. Schools should consider a series of dimensions called the Taxonomy of Intervention Intensity when evaluating the validated intervention program: strength, dosage, alignment, attention to transfer, comprehensiveness, and behavioral support. Then, interventions are organized in a map to support the adults in implementing with fidelity, communicating and coordinating roles, and supporting carryover into other school settings.

Progress Monitoring

Teachers use informal, often unstandardized, assessment approaches to make immediate, real-time instructional changes every day in schools, whereas progress monitoring within an MTSS involves more structured, standardized assessments. Progress monitoring in an MTSS refers to the use of standardized, valid, and reliable tools (e.g., General Outcome Measures, Direct Behavior Rating, Daily Report Card). After sufficient data are collected (e.g., weekly for six to nine data points on reading GOMs), they are graphed and evaluated against the student’s instructional or social-emotional/behavioral goal to determine whether the student is making sufficient progress.

Responsive

After sufficient data have been collected and graphed (e.g., six to nine data points on reading GOMs), progress is evaluated against the student’s instructional or social-emotional/behavioral goal to determine whether the student is making sufficient progress. If the trendline is above the goal or aimline, then the response to the intervention program is adequate to close the gap. We celebrate and continue with the intervention until the goal is reached.

Non-Responsive

After sufficient data have been collected and graphed (e.g., six to nine data points on reading GOMs), progress is evaluated against the student’s instructional or social-emotional/behavioral goal to determine whether the student is making sufficient progress. For social-emotional-behavioral goals, the focus should be on replacement skills and/or behaviors, with progress monitoring measuring growth in that area, which should then correlate with a decrease in problem/maladaptive behavior. If the trendline (performance) is below the goal or aim-line, then the response is not (yet) adequate. We move to the next step in the intensification process. In most cases, students with severe and persistent learning needs, including students with disabilities, will require several rounds of adaptation before progress is sufficient. If at any time the team or a family member suspects a disability, a referral for a special education evaluation should be initiated. The data collected through the intervention and intensification/DBI process can be used in the referral and evaluation processes and to inform existing IEPs and 504 plans.

Diagnostic

When progress in response to an intervention implemented with fidelity is inadequate, the student-level team needs to dig deeper. In this step of DBI, a team engages in a diagnostic process to develop a hypothesis about the potential cause(s) of the student’s academic and/or behavioral difficulties. This hypothesis drives the team’s decisions about how best to support the student and adapt the intervention. In Rhode Island’s model, since academic and behavioral needs don’t exist separately from one another, we conceptualize a diagnostic process that hypothesizes if the need is an “isn’t doing” (i.e., relationship, engagement, and motivation), a “trouble doing” (i.e., difficulty performing the skill automatically and generalizing it to new situations), or a “can’t do” (i.e., skill deficit/instructional mismatch possibly indicating the need for a different intervention). In the social-emotional/behavioral realm, this process may include a simple Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA) (i.e., FACTS), an extensive FBA, or a Collaborative Problem-Solving Assessment of Problems to be Solved and Lagging Skills.

Intervention Adaptation

After completing a diagnostic process and hypothesizing the nature of a student's struggle, the team moves on to plan adaptations to better meet these individual needs. The plan often identifies a clear focus (i.e., addressing barriers to intervention fidelity such as absences, addressing an 'isn’t doing,' a 'trouble doing,' or a 'can’t do' hypothesis). The intensification plan also defines who is responsible for which part of the plan and by when. For some more complex SEB needs, a family-school-organization wrap-around may be needed. A staff member or a Family Care Community Partnership’s partner will function as a coordinator aligned with memoranda of agreement established between the school and community providers. Finally, the team sets a date to come together after implementing the intensification plan to see if it worked. Recall that students with the most complex needs, including students with disabilities, may require several rounds of adaptation before progress is sufficient. The process repeats until we figure it out - together. Go team!

The quality and fidelity of Tier 1 and Tier 2 set the foundation for the successful implementation of intensive intervention. Schools/teams focusing on Tier 3 often find it necessary to improve their Tier 1 and 2 systems as part of continual school improvement to better meet the needs of their most complex learners (National Center on Intensive Intervention, 2022).

Learn More About Tier 3

If you're interested in improving your school's implementation of Tier 3, be sure to check out BRIDGE-RI's strand of courses devoted to this topic. Beginning with the Tier 3 Overview course, you'll learn more about the practices, data, and systems needed to support an effective Tier 3.

Data-Based Individualization, National Center on Intensive Intervention (n.d.) Text-only version of the Data-Based Individualization graphic